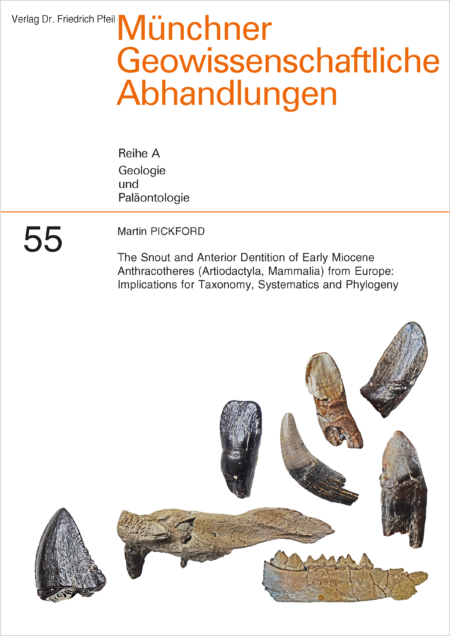

The literature on the Early Miocene, Old World anthracotheres currently classified in the genus Brachyodus, reveals that diverse opinions have been published concerning the interpretation of their anterior teeth, both deciduous and permanent. The European fossil record encompassing the osteology of the snout, and the odontology of the incisors and canines in situ in jaws of these large artiodactyls is poor, with descriptions of only four or five mandibular symphyses that contain teeth and only three premaxillae, of which only one specimen of each contains all the teeth, at least on one side. Furthermore, three of the described mandibles were of juveniles with some unerupted teeth, rendering it difficult to determine whether the partly preserved empty alveoli originally housed deciduous or permanent teeth. In contrast, there are many isolated anterior teeth in museums and private collections. There is also the question of sexual dimorphism which has been difficult to address due to the scarcity of teeth in situ in the jaws, although males and females of some taxa were likely to have been dimorphic and bimodal in some tooth positions (I1/, i/2) but were not so clearly different in other elements of the dentition, especially the molars and premolars.

The present article focuses on several undescribed anthracothere mandibular symphyses and premaxillae from France, Egypt, Kenya and Uganda that throw some light on the matter and it includes a reinterpretation of previously described specimens. However, because so few incisors and canines have been found in situ in jaws, it does not resolve all the issues, especially those concerning the deciduous dentition, because no specimens have been recovered with the anterior milk teeth in situ. It is reasonably clear though, that some early forms previously attributed to Brachyodus possessed three permanent incisors and a canine in the lower jaws, whereas later forms of the genus generally lacked the canines and often the lower central incisors (either suppressing their development entirely or shedding them during ontogeny). Reduction of the quantity of teeth in the incisor row is also likely to have occurred in the upper jaws, with two of the available premaxillae showing the presence of three incisor alveoli, whereas two other specimens show only two teeth in situ.

The sample of mandibular symphyses of large anthracotheres from the Early Miocene of Moghara, Egypt, fall into five morphological categories (Pickford & Abdel Gawad, 2024), but the sample from the French Faluns and the Tagus Basin, Portugal, comprise only two main forms, one of which is fused early in ontogeny and is elongated, referred to Brachyodus, the other shorter and remaining unfused into the sub-adult phase of ontogeny and even when fused in adults, continues to show a suture between the two mandibles. The former group, attributed to Brachyodus, exhibits a marked degree of dimorphism in the tusk-like second lower incisors, with females having more gracile teeth than males. The latter group exhibits weaker dimorphism in the i/2s and is attributed to a new genus, Chitenaymeryx.

A major difference between Chitenaymeryx and Brachyodus is the presence of lower canines in the former genus, but their absence in the latter one. There are also important differences in dental morphology in these two genera.

A revision of the large anthracotheres from Moghara, Egypt, was recently undertaken because studies have revealed that some of the material previously identified as Brachyodus depereti Fourtau, 1918, belongs to Jaggermeryx africanus (Andrews, 1899) (ex naida, Miller et al. 2014), as does most of the material previously attributed to Brachyodus africanus. Other specimens belong to Aegyptomeryx Pickford & Abdel Gawad (2024) the biggest anthracotheres known from the deposits. The species Afromeryx grex Miller et al. 2014, is a junior synonym of Mogharameryx mogharensis (Pickford, 1991). The species Jaggermeryx palustris Miller et al. 2014 was transferred to a new genus Masrimeryx Pickford & Abdel Gawad (2024). There are thus five species of large anthracotheres at Moghara, which are accompanied by four small species: Nov. gen. plus Sivameryx moneyi (Fourtau, 1918,) Afromeryx zelteni Pickford, 1991, and Sivameryx africanus (Andrews, 1914). Some details are provided in Pickford & Abdel Gawad (2024).

This monograph attempts to answer questions regarding the significance of the differences observed in the anterior dentitions of anthracotheres, focussing on the European material. A major conclusion is that there are at least four taxa of anthracotheres in the French Faluns and the Sables de l’Orléanais, three species of which are attributed to Brachyodus, and one to Chitenaymeryx nov. gen. Two new species of Brachyodus are diagnosed.

This monograph looks briefly into the systematic relationships between subgroups of anthracotheres and it also delves into the relationship between anthracotheres and hippopotamids.

Key words: Anthracotheriidae, Europe, Africa, Early Miocene, dentition, snout, taxonomy, systematics.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.